Irresponsible drinking requires regulation to modulate its potential for harm. There are specific neurotoxic effects of alcohol drinking. The responsible individual needs to learn personal skills to refuse alcohol drinking when required to do so. The potential harm to society with irresponsible drinking and driving necessitates regulation at a societal level.

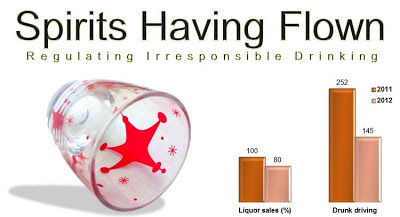

Alcohol drinking and liquor sales were down by 20-30% in September 2012 following a police raid on an unlicensed rural Pune nightspot. The uproar by its patrons and subsequent police action on liquor retailers and other restaurants resulted in the Pune District Wine Traders Association lamenting the impact of plunging alcohol sales at premium outlets and lounge bars.

References

Regulating irresponsible drinking

Alcohol drinking and driving in Pune over New Year's eve was markedly reduced as compared to last year. This year 145 drunk driving arrests were made as against 252 last year. This reduction was despite an increase in the total number of arrests made in Pune for irresponsible drinking and driving in 2012 as compared to the previous year. The heightened deployment of police personnel manning 30 prominent points of the Pune roads on New Year's eve was apparently deterrent enough.Alcohol drinking and liquor sales were down by 20-30% in September 2012 following a police raid on an unlicensed rural Pune nightspot. The uproar by its patrons and subsequent police action on liquor retailers and other restaurants resulted in the Pune District Wine Traders Association lamenting the impact of plunging alcohol sales at premium outlets and lounge bars.

Is regulation effective?

The effects of regulating alcohol drinking have been specifically studied.- In Kentucky — the birthplace of bourbon whiskey and the home of many distilleries — dry districts had less alcohol-related auto accidents and drunk driving arrests. This should cheer the citizens of Chandrapur which will be the third district in Maharashtra state to go dry in a bid to curb irresponsible drinking.

- In Alaska, isolated villages that prohibited alcohol had lower rates of serious injury resulting from assault, and motor vehicle collisions. A local police presence in these dry villages further reduced the incidence of assault

References

- Darryl S. Wood, Paul J. Gruenewal. Local alcohol prohibition, police presence and serious injury in isolated Alaska Native villages. Article first published online: 27 FEB 2006 DOI: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01347.x

- Wilson RW, Niva G, Nicholson T. Prohibition revisited: county alcohol control consequences. J Ky Med Assoc. 1993 Jan;91(1):9-12.